I, like many Americans, read F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby in high school. Although I remember little of the specifics, I know I found it insufferable and deeply uninteresting. Even as a teenager I was already tired of reading about and discussing rich heterosexual white people and their petty, self-centered problems. I’m sure I saw the movie with Leonardo DiCaprio, but all I’ve retained of it is the gif of him raising his champagne glass in a toast and that meme of grumpy Leo sitting on a couch. In short, I do not care about The Great Gatsby. I do, however, very much care about a fantasy retelling of it featuring a queer Vietnamese girl. That is extremely my jam.

For Jordan Baker, the Jazz Age is a time of magic and manipulation. Spells and curses and infernal pacts permeate every strata of society, but especially the top where she resides. The summer of 1922 begins like any other, but ends as one of the defining periods of her life. That is the summer Jay Gatsby barges back into their lives, bringing with him chaos and destruction. Jay wants Daisy, the closest thing Jordan has to a best friend, but Daisy long ago rejected him and settled for Tom, a philanderer more interested in his side piece than his family. Daisy also wants Jay, but is unwilling to give up her highly cultivated lifestyle to be with him. Jordan and Nick, an old acquaintance of Jay’s and Jordan’s current fling, find themselves in the unenviable position of being used and abused by the star-crossed lovers. Jay’s volatile nature mixed with Daisy’s emotional instability and Tom’s casual cruelty form a toxic hurricane from which Jordan and Nick will not emerge from unscathed.

Jordan Baker has a lot of privilege but little of the power held by her white compatriots. Nick treats her like a person, but everyone else—Jay, Tom, and Daisy included—treat her like an exotic toy or pet. They ignore her Vietnamese heritage to the point of colorblindness, which allows them to demean other Asian immigrants while simultaneously tokenizing her and pummeling her with microaggressions. Having been “rescued” by a rich white woman as an infant, Jordan was denied knowledge of her cultural traditions. She’s bold enough to push back on anti-Asian racism, but has little defense other than her quick, dry wit. It’s enough but not enough. Jordan is the only Asian person most of her peers will ever know. It’s up to her to defend an entire continent of people, not just her own culture, and she must do it with little practical knowledge of what her people are like.

She is spared the worst of the anti-Asian vitriol by virtue of her high social rank gifted to her by her inherited wealth, but she is still subject to systemic oppression. Throughout the novel, the Manchester Act, a bill that would expel Asians from the United States, looms large. The bill did not exist in the real world but does have real world parallels. The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 (extended for another decade by the Geary Act of 1892) prohibited the majority of Chinese immigration; women had largely been banned since the Page Act of 1875, and even before that it was difficult for them to gain entry. There were several other laws enacted, but the big one was the Immigration Act of 1924 which prohibited immigration from the rest of Asia (except for the Philippines, then an American colony) and set in place strict and very low quotas from “less desirable” nations in south and eastern Europe. As she was born in Tonkin, or northern Vietnam, Jordan will be subject to the Manchester Act if passed, and no amount of wealth or connections can exempt her.

Jordan has another layer to her identity that marks her as other: She’s queer. In an era where the patriarchy and white supremacy are clamping down on anyone deemed different, Jordan revels in her queerness. Although she treats her conquests as dalliances, they are also a kind of armor. As long as she is flitting from one relationship to another, she never has to open herself up to something real. She can protect herself from being hurt, but it comes at the cost of never being truly known.

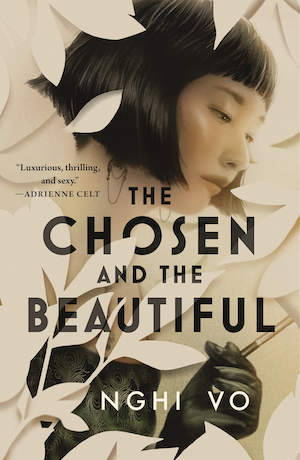

Buy the Book

The Chosen and the Beautiful

For much of the novel, Jordan is paired up with Nick, but that doesn’t stop her from dabbling with other people across the gender spectrum. Nick’s attention is pulled toward queerness as well. He has an on again, off again fling with Jay Gatsby, even as Jay obsesses over Daisy. There is a casualness to their relationships with each other and others, but it’s the calculating kind. Nick is too wrapped up in his Midwestern naivety to do much other than flush with embarrassment when others bring up his Jay affair. Jay, meanwhile, seems to see Nick as a power trip. He cannot have Daisy, so he takes someone else, someone a bit too flustered to commit to but just innocent enough to push around however he likes. There’s a line in the book that makes me think Daisy may be queer as well, albeit on a different part of the spectrum as her friends.

Vo has always demonstrated a talent for vivid and imaginative descriptions, a skill she turns up to eleven in The Chosen and the Beautiful. The narrative style Vo chose feels very different from The Singing Hills Cycle, but it is just as exquisite. It fits perfectly with the era. It feels like something Fitzgerald or Evelyn Waugh might have written, minus the sexism, racism, and colonial mindset. The language is sumptuous and a little bit florid, like a flapper dress studded in crystals and beads.

What Nghi Vo does with The Chosen and the Beautiful is nothing short of phenomenal. The novel dazzles as much as it cuts. Vo does The Great Gatsby far, far better than Fitzgerald ever did. Might as well reserve a spot on next year’s award ballots now, because this one will be hard to beat.

The Chosen and the Beautiful is available from Tordotcom Publishing.

Read an excerpt here.

Alex Brown is a librarian by day, historian by night, author and writer by passion, and a queer Black person all the time. Keep up with them on Twitter, Instagram, and their blog.